TL;DR: What follows is a long (good Instapaper material), highly-technical post about re-building Instapaper’s full-text search feature. I’d recommend at least a rudimentary understanding of Amazon Web Services before continuing. If you’d like to read about the product launch, which should be friendly for everyone, you can read the blog post on the Instapaper blog.

I’ve been embarrassed about Instapaper’s full-text search for some time now…

Instapaper’s full-text search is available to Premium subscribers only, and it was originally set up as a Sphinx server to be used in conjunction with Instapaper’s MySQL database. The Sphinx server creates and manages full-text indexes over the MySQL search data, and Instapaper performs full-text search requests directly to the Sphinx server using a SQL-like syntax.

Instapaper’s full-text search box has been the most fragile and difficult to manage part of the system. Since making the transition to Amazon Web Services, Instapaper’s full-text search has run on a single m2.4xlarge EC2 instance, a memory-optimized instance with ~70GB of RAM. The Sphinx full-text indexes are stored in a 4TB mounted volume, which is a RAID10 array configured as 8 1TB EBS volumes.

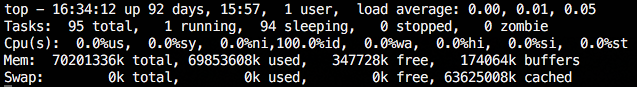

Despite the search service being Instapaper’s largest single point of failure, we’ve run the service with almost 100% uptime over the past three years (with one brief outage a few months ago during scheduled maintenance). However, throughout 2015 we started to get an increasing number of complaints about the service being slow, requests timing out, and other intermittent reports and complaints. A quick inspection of the system revealed the issue:

The size of the indexes on disk had grown to 2.2TB, and a majority of the system’s memory was dedicated to holding data from the index files in memory. Because the size of the indexes had grown so large and only a small portion of the indexes could be cached in memory, queries on the indexes resulted in unacceptably long response times and, in some cases, timeouts for the end user.

Picking a Solution

An easy solution to the memory availability issue would be to set up a new Sphinx box running on an instance with a larger memory footprint. An r3.4xlarge instance would have increased the total system memory by 75% with only an 8% cost increase; however, increasing the memory footprint would have just masked the real issue.

The crux of the issue is that with the amount of data we have indexed, it’s no longer suitable to run our full-text search with a single machine. In order to continue scaling with the amount of indexed data, the indexes need to be spread across a cluster of search machines. Recreating our Sphinx server on a machine with a larger memory footprint would just be kicking the can down the road a bit further.

Picking a solution turned out to be easier than anticipated as Amazon Web Services had launched a hosted elasticsearch service in October 2015, which is designed for full-text search across distributed data and with high availability. Additionally, elasticsearch comes with a very simple REST API, excellent first-party libraries, great documentation, and a very active development community.

Tuesday 4/19: Setting up the Cluster

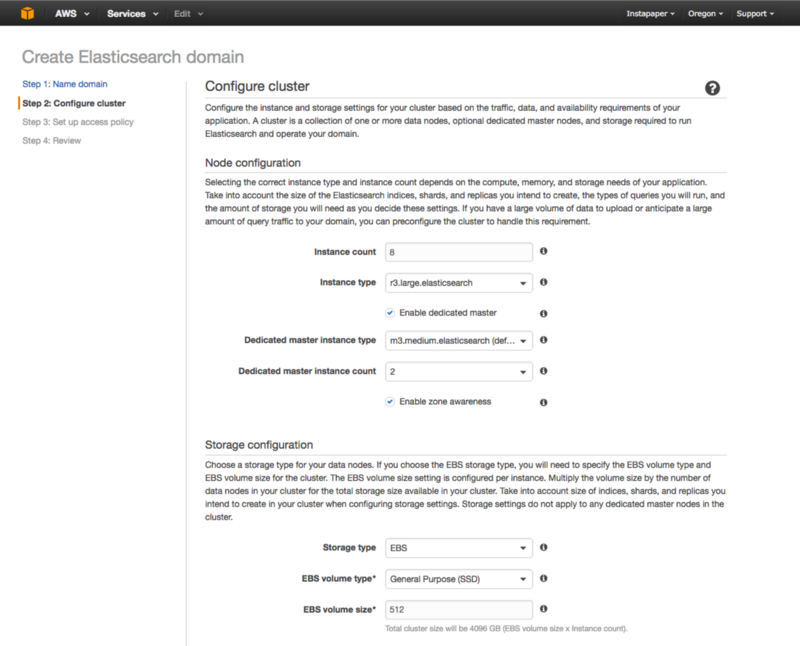

The goal for configuring the hosted elasticsearch cluster was to find the optimal point between storage, availability, and cost requirements. The parameters for setting up a cluster are number and type of data instances, number and type of master instances, and storage options:

As a starting point, I wanted to ensure that the cluster had enough storage space in aggregate to store the existing 2.2TB of data with at least a year’s worth of additional capacity. I decided to create the cluster with 4TB of capacity for the following reasons:

- We currently index ~110GB of data for Instapaper Premium users each month.

- Assuming the rate of data indexed remains constant and the size of the Sphinx indexes are equal to the elasticsearch indexes, that gives us 16 months of additional capacity ((4TB-2.2TB)/110GB=16 months).

- 4TB is the size of our existing search server’s storage.

Each data instance can have an attached EBS volume with a maximum size of 512GB, so the cluster needed 8 data instances in order to achieve the 4TB capacity, and to ensure disk performance I chose provisioned IOPS SSDs with 1,000 IOPS.

For instance types, I decided on memory-optimized instances since these machines would have to hold a large amount of data in memory, and I settled on r3.large.elasticsearch instance types mainly due to reasonable pricing. The total cost of the cluster is roughly 40% cheaper than what it costs to run our existing search server.

In order to ensure high availability with fault tolerance, we set up dedicated, zone-aware master instances for the elasticsearch cluster. The default number of master instances suggested by Amazon is three, however, there is currently a 10 instance limit within a hosted elasticsearch cluster. Given that we needed 8 data instances to satisfy our 4TB capacity requirement, we could only proceed with two dedicated master instances.

A Caveat on Cluster Size

With the current 10 instance limit on hosted elasticsearch clusters, it wouldn’t be possible for us to expand capacity of the cluster without compromising its reliability (i.e. removing one of our two dedicated master instances). As there are storage-optimized instances that come with a 800GB drive attached, I briefly entertained setting up a cluster of five storage-optimized instances to create a 4TB cluster with the option to expand it to 6.4TB. Unfortunately, that would also increase the monthly cost of the service by 60%.

Essentially, I’m making a wager that it’ll be worth the cost savings over the next year to go with a cluster that is capped at 4TB. Hosted elasticsearch is a new service offered by Amazon and I’m betting that within the next 16 months, the arbitrary 10 instance limit will be lifted. Otherwise, I’ll have to re-create the cluster with the more expensive storage-optimized instances.

Thursday 4/21: Indexing First Users

After setting up our production cluster, I proceeded to create a development cluster with one instance to run against my development environment, and I wrote a script that would allow me to iterate over a user’s articles, parse each article, and index the result in elasticsearch.

After indexing the articles on my test account, I set up our front-end search handler to use elasticsearch if the current user is an admin and, otherwise, use the old Sphinx search.

The final step before going to production was to ensure that as Premium users saved and deleted articles the elasticsearch indexes were updated. When articles are saved or deleted in Instapaper, a number of celery-powered worker tasks are generated to handle additional work. Within the save and delete article code paths I created new worker tasks to update the index in elasticsearch, as well.

Finally, after deploying the new elasticsearch worker tasks into production, I back indexed all of the admin users articles so we could test the full-text searches against the new elasticsearch cluster. We demoed the performance differences during betaworks’ weekly all hands meeting and, needless to say, it performed way faster than our existing Sphinx setup.

Tuesday 4/26: Back Indexing Premium Users

The biggest challenge for rebuilding Instapaper’s full-text search was to index the 75 million articles saved by Instapaper Premium users.

The script I wrote to back index the three admin users’ articles executed linearly by iterating over each admin user, then all of the articles for each user, parsing each article, and adding the parsed text into the elasticsearch index. This process took a few hours for a few thousand articles, but would have taken the better part of a year to do all 75 million articles.

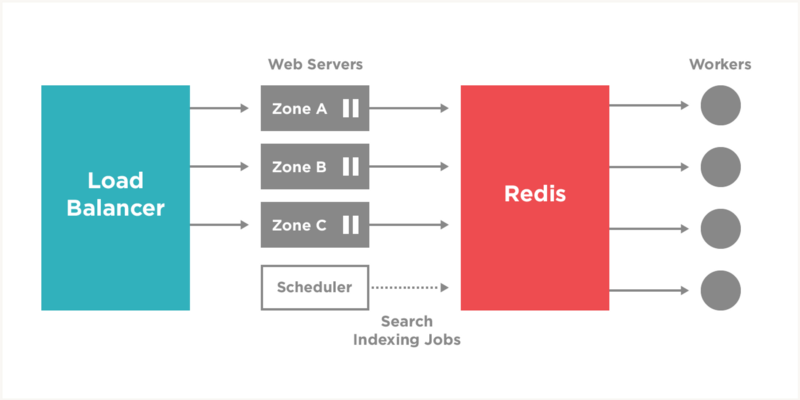

When writing the back indexing script, the goal was to complete the indexing as quickly as possible using our existing infrastructure without affecting the core service, so I decided the script would simply add jobs to a celery queue and the four worker machines would process those jobs to achieve parallelization.

To start, I set up a new celery queue bulk_search and created two jobs for that queue. The first job, bulk_update_elasticsearch, receives an article ID as parameter and indexes that article in elasticsearch. The second job, bulk_add_articles_to_elasticsearch, receives a user ID as a parameter, iterates over all of the user’s articles, and creates bulk_update_elasticsearch jobs for each article.

By creating a separate job queue for these tasks, I would ensure that jobs for our core service wouldn’t be affected by the influx of new jobs for back indexing into elasticsearch. I then configured the four worker machines to run 15 processes each to execute jobs from the bulk_search queue.

Lastly, I wrote the back indexing script to iterate over all of the Instapaper Premium users, queueing a bulk_add_articles_to_elasticsearch job for each user, and added a bit of code that would cause the script to sleep for 30 seconds if the bulk_search queue had more than 2,000 jobs in it.

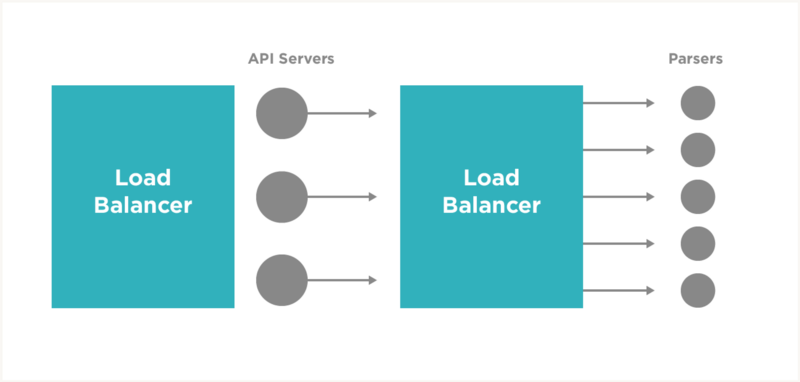

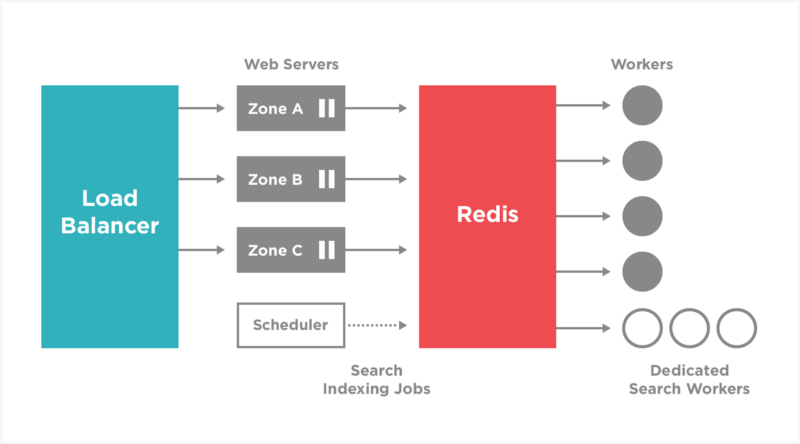

I started running the back indexing script on the machine we use for scheduled tasks at around 4PM that afternoon, and continued monitoring the tasks until leaving work that evening. Here’s a backend diagram that illustrates the pieces of the system that handle our redis-backed celery jobs:

Wednesday 4/27: Dedicated Search Workers

At around 10AM I looked at the past 18 hours’ worth of data and found we had only back indexed just under a million articles, 1.3% of the total. At that rate, it would take roughly two months to index the remaining 74 million articles. I also found that the bulk_search job queue had over 2 million jobs in it that were slowly draining, which was causing the back indexing script to sleep for long periods of time.

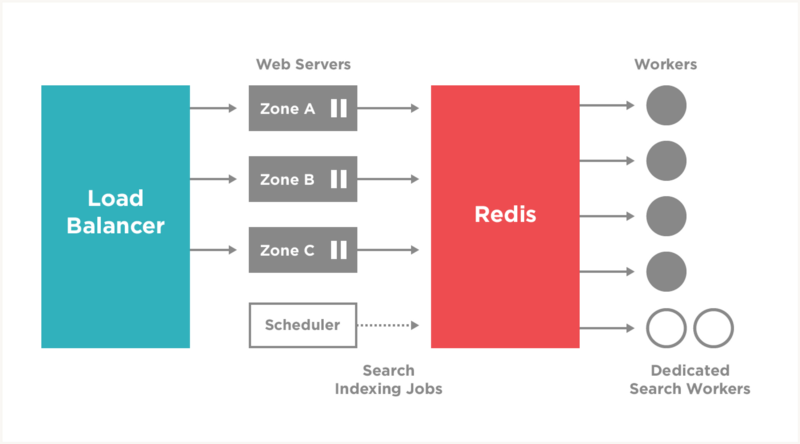

In order to increase the indexing rate to something more acceptable, it was necessary to spin up dedicated worker instances that would only process jobs from the bulk_search queue. I decided to go with EC2 spot instances because I didn’t need these instances to stay around for long, if they were turned off it wouldn’t be critical, and it would be cost effective.

I placed four spot instance requests for dedicated workers, set up new configuration targets for the dedicated search workers, and configured the new targets to run 105 bulk_search processes per machine.

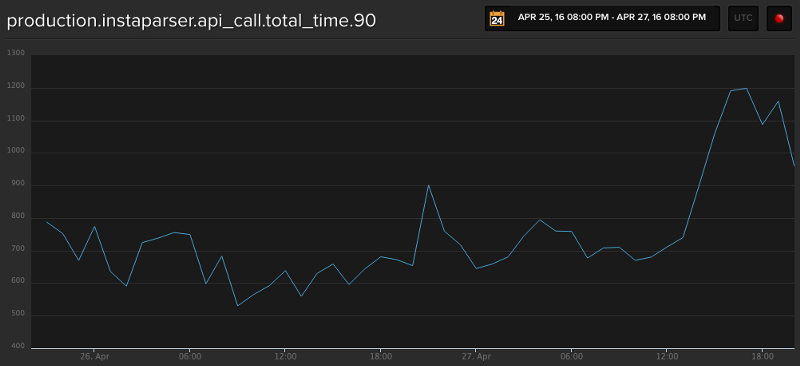

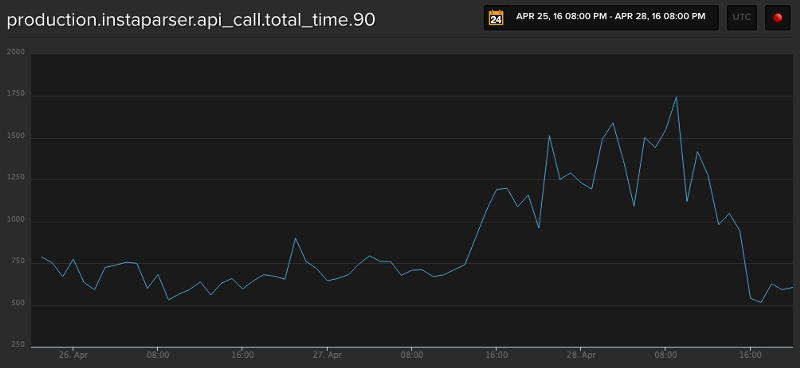

My major concern with scaling up the dedicated workers was causing overhead to our Instaparser infrastructure, which is shared with Instapaper and Instaparser customers. Around 1PM, I added two of the dedicated search workers to bring the number of workers from 60 across four machines to 270 across six machines:

After adding the search workers, I continued to monitor the total time for Instaparser API calls:

From 1PM through 8PM there was a 33% increase in total time for processing Instaparser API calls, and I tracked the increase in time to parses on older URLs, whose domains which were taking 3–6 seconds to respond to requests. It did not appear that this increase affected the core Instapaper service, and I called it a day around 8PM.

Thursday 4/28: Enterprise Instaparser

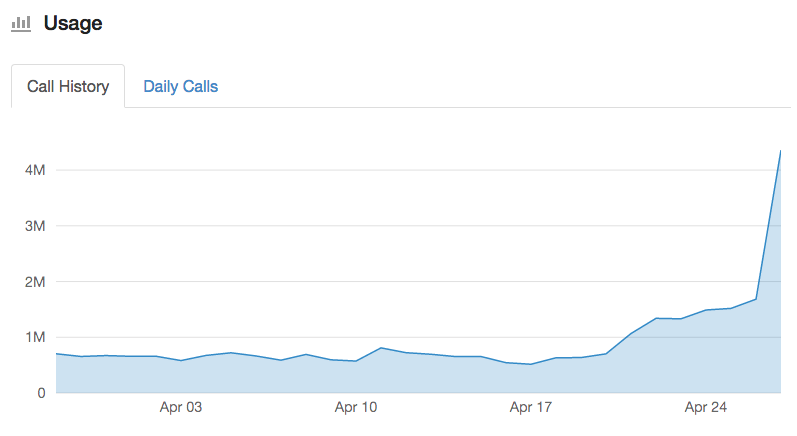

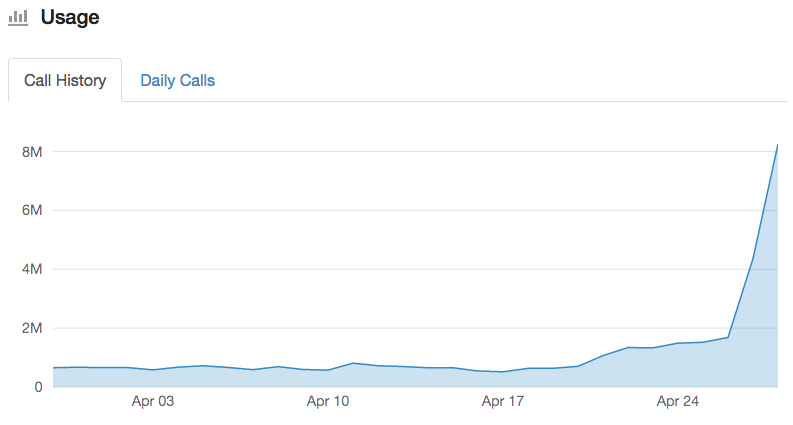

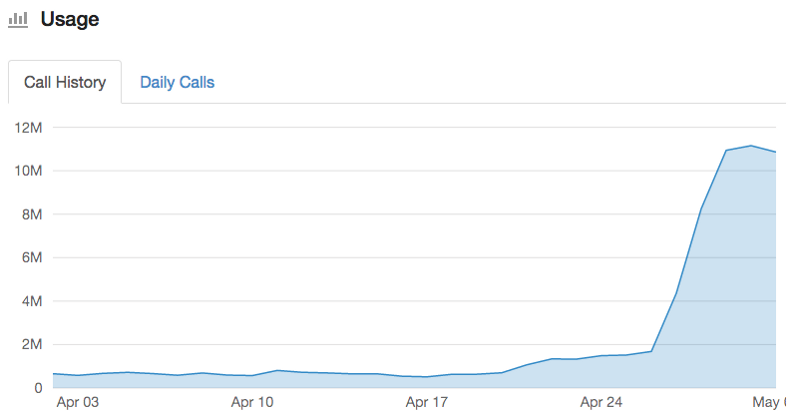

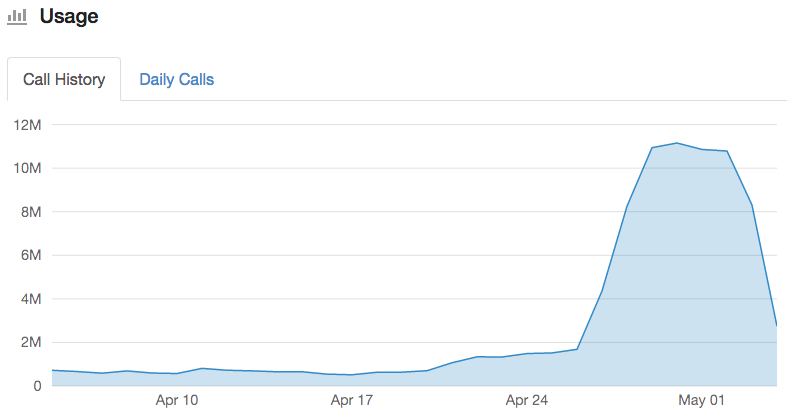

When I arrived in the morning, I logged in to the Instaparser dashboard and I was happy to see we completed over 4 million parses on the 27th:

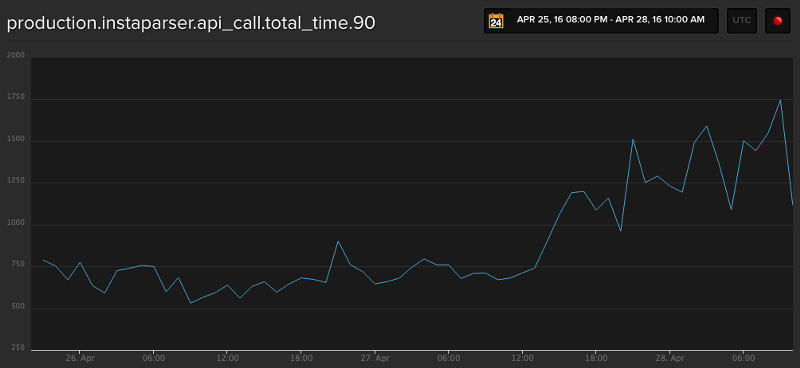

Having dedicated workers increased the new rate of indexing from 1 million articles to 6.5 million articles every 20 hours. At the new rate, it would only take about 11 days to complete the remaining 68 million articles. However, I also found that the metrics around total parsing time had ballooned from an average of 1.1 seconds to over 1.5 seconds overnight:

Due to concerns about increased parsing times affecting the main service and becoming a bottleneck for the back indexing process, I decided to create a dedicated Instaparser cluster that would only be used for the search back indexing. Effectively, this is a similar set up that we are offering for the Instaparser Enterprise plan.

Again, I used spot instances to set up another 8 servers: 3 to operate the Instaparser API which acts as a proxy to 5 internal parsers. Here is an illustration of the Instaparser architecture:

I set up “search” configurations for both the Instaparser and the Instapaper applications that had the same configurations as our normal production settings, except they were both configured to use the dedicated search infrastructure.

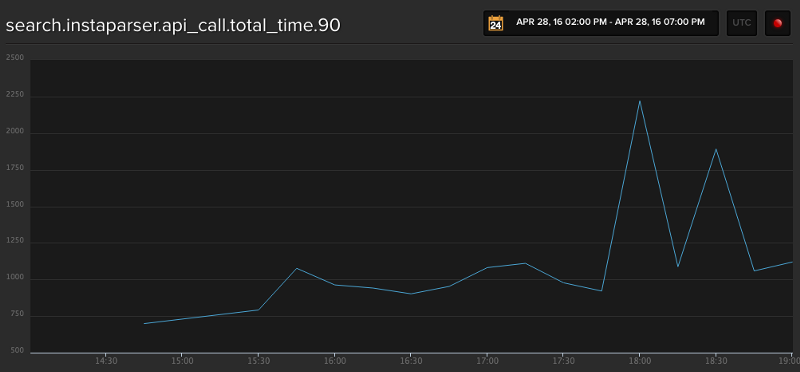

After completing the Instaparser Enterprise cluster and testing it, I set the dedicated search workers to use the new “search” configuration and restarted the processes, continuing to monitor the total time for API calls for our production Instaparser service:

And also the total time for API calls on our new “search” Instaparser Enterprise service:

Friday 4/29: Limits of Scaling

In the morning, I took another look at how many parses we were now able to do with the dedicated parsing infrastructure, and on the 28th we parsed over 8M articles, compared to 4M the day before:

The Instaparser Enterprise service allowed us to increase our rate of indexing by 20%, from 6.5 million to 7.8 million, in a 20 hour window. With the increase of rate in indexing, it would take another 8 days to parse and index the remaining 60 million articles.

Given that the search indexing and parsing were now running on totally dedicated services, I decided it would be good to add a third dedicated search worker to increase the rate of parsing even further. The additional machine would increase the number of worker processes by 40%, up to 375 from 230, and the configuration is illustrated below:

After adding the additional search worker machine, I began monitoring all of the systems when I noticed that we were starting to get a high volume of errors coming from the bulk_update_elasticsearch worker tasks:

EsRejectedExecutionException[rejected execution (queue capacity 200) on org.elasticsearch.action.support.replication.TransportShardReplicationOperationAction

It appears that the additional search workers were now causing the hosted elasticsearch cluster to reject some of the index requests because we were exceeding the allowed queue capacity. In short, we were now parsing and indexing faster than our hosted elasticsearch could write the indexes, and some portion of indexed articles were failing.

Some light Googling showed that elasticsearch settings can be tweaked to increase the number of threads, queue size, etc. to alleviate the above issue. However, at this time those options are not available in the hosted elasticsearch settings. After determining that only .02% of indexed requests were failing and making sure that the error logs were available to re-index those articles, I decide to keep the third worker running over the weekend to accelerate the rate of indexing even further.

Ultimately, the limit to our scaling was the hosted elasticsearch cluster itself.

Monday 5/2: Search Features

Adding the third search worker machine on Friday increased our rate of indexing by an additional 18%, bringing us to an average 11 million articles parsed and indexed per day:

That brought the total number of indexed articles to 47 million, with only 28 million articles remaining to be indexed. With 11 million articles being parsed and indexed today, that meant we would finish back indexing all of the Premium users’ articles by mid-day Wednesday.

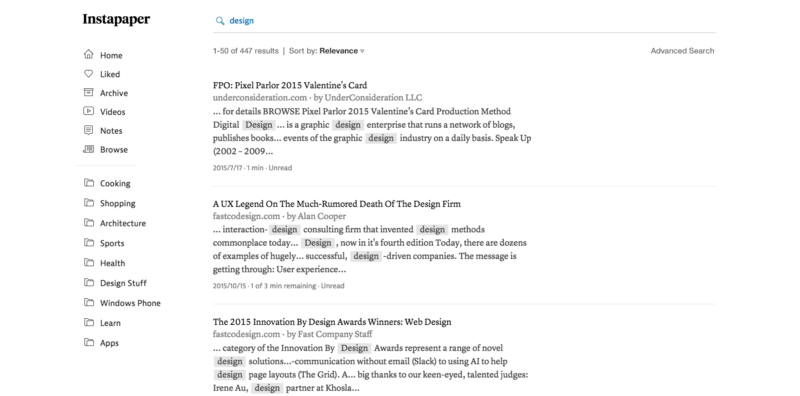

After updating the team with the timeframe, to completing this task, we set a tentative launch date for Thursday 5/5. Rodion Gusev, who heads up support, community, and copywriting, took the lead on drafting the launch blog post and Aaron Kapor, our design director, had been working on mockups for some additional search features made possible by elasticsearch:

The main features we were planning on adding were paginated results (previously we only showed the most recent 50 matches), sorting options for relevance or chronology (previously only reverse chronological), and advanced filters for searching by author or domain.

Thursday 5/5: Launch Day

Over the previous few days we had finished editing the blog post, implemented all of the additional search features, and completed back indexing all of the Premium users’ articles:

We scheduled one of betaworks’ QA interns to come in Thursday morning and run through a checklist and attempt to find some corner case issues. After running through the checklist and only finding one minor issue, we decided to move ahead with the launch and address the issue after launching.

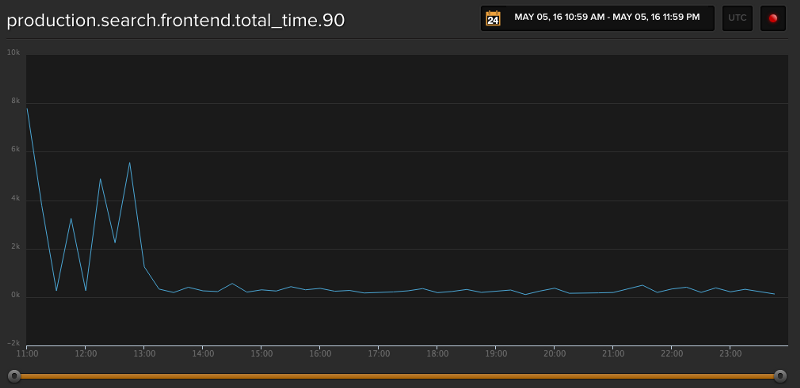

Here’s a graph showing the total time for search results before and after launching:

Our search went from an average query time of 3 seconds (horribly embarrassing) to 250 milliseconds with several new features that really improved the quality of the full-text search product.

Friday 5/6: Winding Down & Learnings

After launching on Thursday, I spent most of Friday cancelling our spot instance requests, winding down the workers and the Instaparser Enterprise cluster, and generally performing the rest of the clean up required after from scaling up for the back indexing of all 75 million of Instapaper Premium users’ saved articles.

Projects like this are part of the reason I really love working on Instapaper. I learned a ton about search software like Sphinx and elasticsearch. I went from not knowing anything about setting up an elasticsearch cluster to making cost and capacity decisions on a 4TB cluster, indexing over 2.2TB worth of data in the cluster, and leveraging a lot of elasticsearch features to set up new consumer-facing features for our search offering. And that was all in just 16 days!

I also learned a ton about the Instapaper system, how to scale up quickly, where the bottlenecks in the service are under load, and how to overcome those bottlenecks to push further performance in the system.

I’d love to hear your thoughts, questions, or criticisms via email to brian@team.instapaper.com, or on Twitter.